A battery consists of various materials, among which four key components are considered the primary determinants of its performance: the cathode, which releases lithium ions; the anode, which stores energy; the electrolyte, which serves as a pathway for lithium ions; and the separator, which divides the cathode and anode.

For these key components to perform their intended functions, various other components that support them must serve their roles. Among them is one that may not stand out but helps maintain a stable electrode structure: the binder.

*Want to learn about binders from the basics? Check out the Battery Glossary – Binder

Gaining Attention with the Development of Next-generation Materials

The cathode and anode are produced by coating a mixture called slurry onto the current collector. This slurry is made by mixing active materials, conductive additives, binders, and a solvent in specific ratios. Among these, the binder helps active material and conductive additive particles adhere more effectively.

Recently, demand for high-capacity, high-performance batteries has increased across various sectors, including EVs, ESS, and electronic devices. To meet this demand, research is underway to develop next-generation active materials with higher energy density, such as silicon and lithium metal. However, these materials are challenging to commercialize due to issues like volume expansion and interfacial reactions that destabilize the electrode structure. Accordingly, researchers are exploring new materials and technologies to overcome these limitations.

As a result, binders must become more advanced to support the properties of next-generation active materials. They should go beyond serving merely as adhesives, contributing instead to maintaining electrode stability and enhancing ionic conductivity.

Requirements for Higher Battery Performance

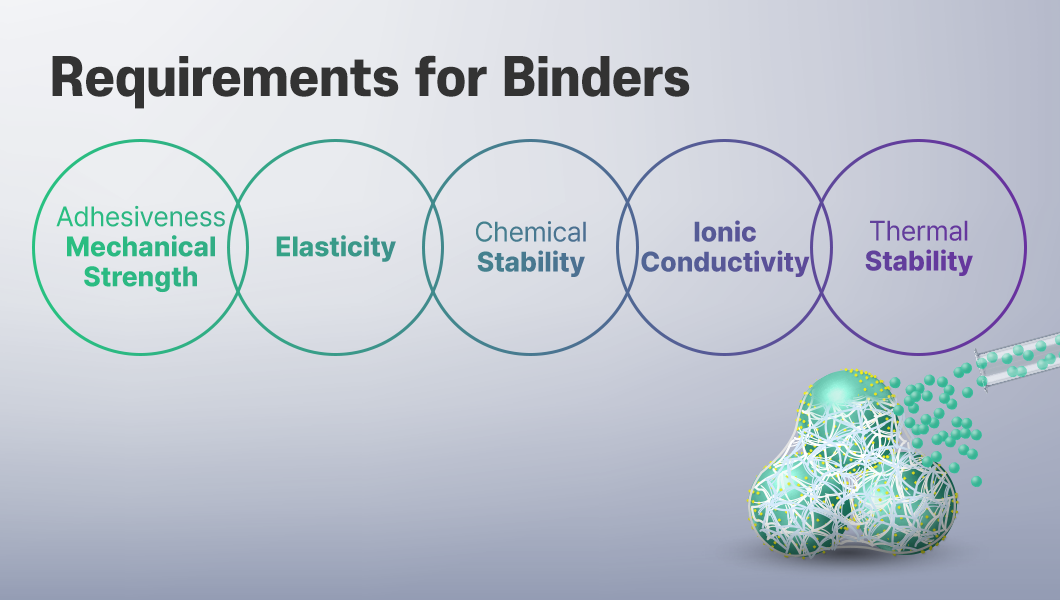

So, what are the requirements for binders to support a stable electrode structure and improve battery performance?

The first is adhesiveness, which holds active material and conductive additive particles together, along with sufficient mechanical strength. This is because the electrode structure remains stable only when these particles stay firmly bonded, even during charging and discharging.

Next is elasticity. Materials such as silicon, which expand and contract during charging and discharging, require more than just adhesiveness. They need properties that can relieve the stress1 caused by repeated volume changes.

Another important factor is chemical stability. Because the binder is in direct contact with the electrolyte, it must stay stable during the redox reactions occurring within the electrode, while effectively suppressing degradation, corrosion, and gas generation that may take place at the interface. Maintaining this interfacial stability is essential to ensuring the long-term lifespan of the electrode.

In addition, binders should not hinder the movement of ions and electrons within the electrode, making it important to maintain a structure that does not compromise ionic conductivity.

Lastly, thermal stability is necessary to ensure consistent performance under various temperature conditions. Since batteries are used in diverse environments, they must be able to retain their shape even in high-temperature conditions.

Non-Aqueous and Aqueous Binders Classified by Solvent Type

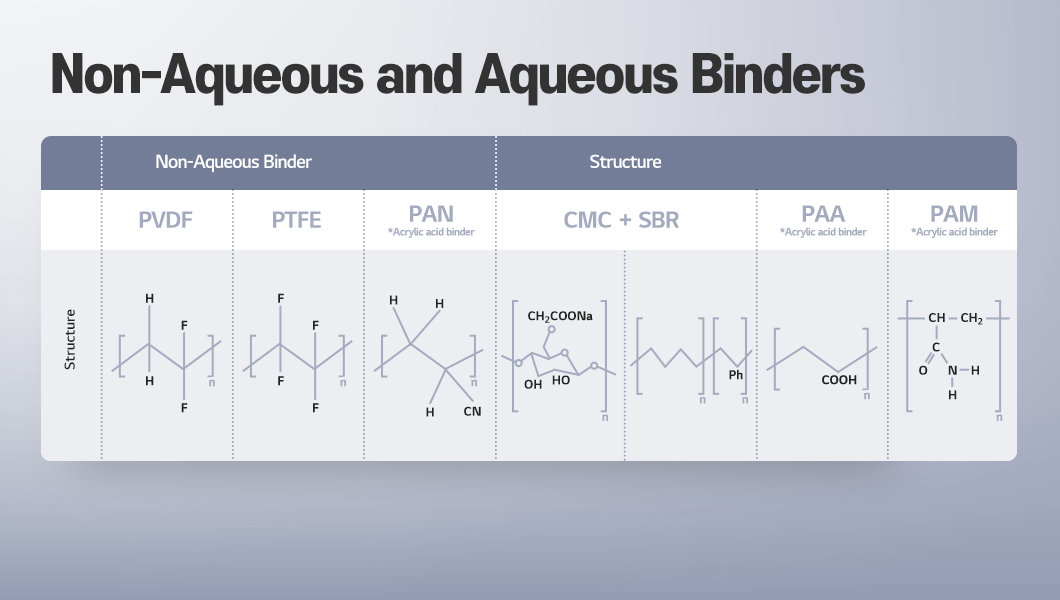

Binders are classified as non-aqueous (organic) or aqueous, depending on the type of solvent used. Non-aqueous binders are applied by dissolving it in organic solvents such as NMP (N-methyl-2-pyrrolidone) and are typically used for cathode active materials, as these materials do not disperse easily in water. In contrast, aqueous binders use water as the solvent and are widely applied in anode manufacturing.

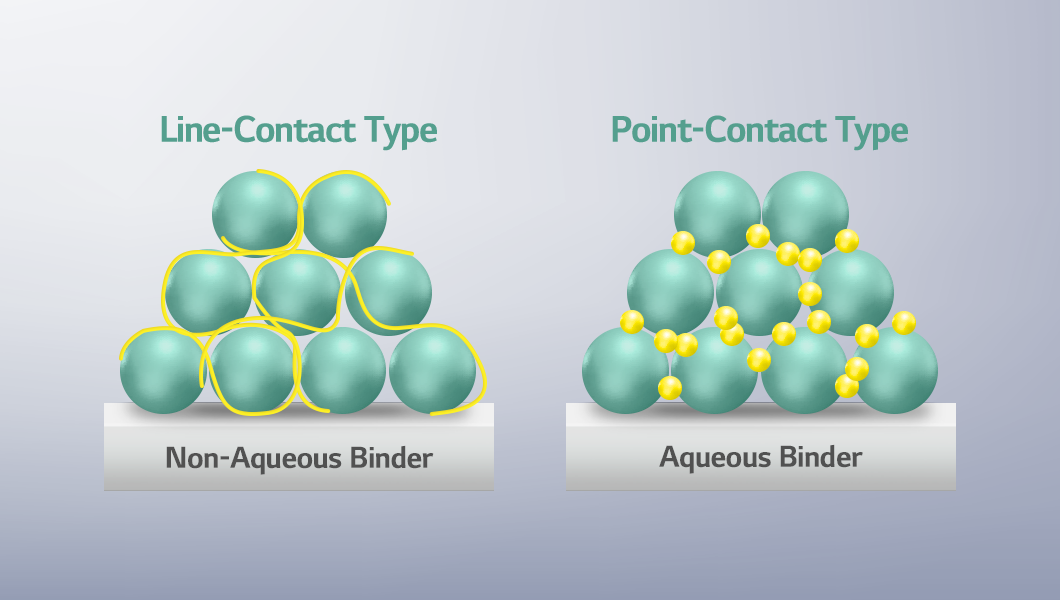

Non-aqueous and aqueous binders also differ in the bonding structure between particles and binders. Non-aqueous binders form a “line-contact” structure, connecting particles in a continuous line, whereas aqueous binders create a “point-contact” structure, joining particles at contact points. This difference can affect the mechanical strength and overall performance of the electrode.

To achieve higher battery energy density, recent studies have focused on raising the proportion of active materials. Accordingly, aqueous binders are becoming more widely adopted, as they allow for a higher active material ratio while reducing binder content. In addition, because they do not use organic solvents, they help lower environmental impact, simplify the process, and reduce manufacturing costs. They also enhance drying speed, thereby improving manufacturing efficiency. Furthermore, aqueous binders exhibit high affinity with the electrolyte and excellent electrochemical stability.

Non-Aqueous Binder: PVDF (Polyvinylidene Fluoride)

One of the most common non-aqueous binders is PVDF. It has been widely used since the early days of lithium-ion battery commercialization and is typically applied together with the solvent NMP (N-methyl-2-pyrrolidone). This combination provides excellent adhesion, good dispersion of conductive additives, and high stability during redox reactions.

In particular, PVDF demonstrates excellent thermal and electrochemical stability, supported by the strong carbon–fluorine bonds within its molecular structure. It retains a stable electrode structure even at voltages around 5 V and at temperatures approaching 400 °C. In addition, PVDF exhibits high crystallinity due to its linear polymer structure, and ensures high ionic conductivity by expanding up to 30% when absorbing electrolyte.

However, the solvent NMP used with PVDF is highly toxic and expensive to process. As a result, the battery industry is exploring ways to improve both environmental sustainability and cost efficiency.

Non-Aqueous Binder: PTFE (Polytetrafluoroethylene)

PTFE is a fluoropolymer whose molecular structure consists entirely of carbon–fluorine bonds. These strong bonds provide excellent thermal and chemical stability, as well as high mechanical strength. As a result, PTFE sustains structural integrity even under extreme conditions such as high temperature, high pressure, and high voltage.

PTFE is particularly recognized as a key binder in the dry electrode process, a next-generation manufacturing technology, due to its fibrillation property. When stress is applied, PTFE particles stretch and transform into fine fibers. These fibers interweave with each other, allowing the structure to be maintained without a substrate. Consequently, a stable electrode film can be formed, making PTFE an optimized material for the dry electrode process.

Aqueous Binder: CMC (Carboxymethyl Cellulose) + SBR (Styrene-Butadiene Rubber)

CMC and SBR are the most widely used combination of aqueous binders for lithium-ion battery anodes.

CMC is a natural cellulose-based linear polymer derivative with high viscosity and excellent water solubility. It binds tightly with active materials within the electrode, enhancing structural stability. Thanks to such properties, it can be effectively applied to silicon anodes whose volume changes significantly during charging and discharging. In addition, CMC forms strong chemical bonds with the silicon surface, improving interfacial stability and suppressing electrolyte decomposition reactions. Furthermore, it helps disperse active materials and maintain phase stability within aqueous slurry systems.

SBR, used together with CMC, is a rubber-based polymer that enhances adhesiveness. When combined with CMC, it forms a point-contact structure among electrode particles, improving mechanical flexibility and friction resistance, which ultimately contributes to a more stable electrode structure. In other words, CMC ensures structural stability, while SBR adds adhesiveness and flexibility. The combination of these two binders is commonly used in electrodes with graphite active materials, and is also applied in composite electrodes that combine graphite and silicon.

Acrylic-based binder: PAA (Polyacrylic Acid), PAN (Polyacrylonitrile), PAM (Polyacrylamide)

High-capacity anode active materials such as silicon undergo volume expansion during charging and discharging, which can affect the electrode structure and lifespan. To address these limitations, acrylic-based binders such as PAA, PAN, and PAM are being developed. These materials are formulated as copolymers2—combinations of PAA with PAN or PAM—instead of using PAA alone, allowing them to complement each other’s strengths and weaknesses.

PAA (Polyacrylic Acid) is an aqueous binder that is an acrylic polymer formed by the repeated bonding of acrylic acid monomers containing carboxyl groups (–COOH). The strong bond between carboxyl groups and hydroxyl groups (–OH) on the silicon surface allows the binder to adhere firmly to silicon particles. This structure prevents the electrode from collapsing easily and maintains interfacial stability even after repeated charging and discharging, while also reducing side reactions such as electrolyte decomposition. However, when the carboxyl groups bond too strongly and harden, the structure can become brittle, making it vulnerable to volume changes.

Another aqueous binder, PAM, is an acrylic polymer formed by the repeated bonding of acrylamide monomers containing amide groups (–CONH₂). Because amide groups can form multiple hydrogen bonds, PAM interacts strongly with hydroxyl groups (–OH) on the silicon surface, allowing the binder to adhere firmly to silicon particles. In addition, PAM is highly flexible and can accommodate the volume expansion and contraction of silicon that occur during charging and discharging. However, its adhesion to ions is weak because it lacks carboxyl groups.

Lastly, PAN is an acrylic polymer composed of acrylonitrile monomers containing nitrile groups (-C≡N) and is classified as a non-aqueous binder. The nitrile groups form strong bonds with the hydroxyl groups on the silicon surface, helping active material particles adhere firmly together. This contributes to maintaining the electrode’s structural stability. Additionally, PAN’s high electrical conductivity at low temperatures facilitates smooth lithium-ion movement, while its strong thermal resistance at high temperatures supports consistent performance. However, its low water solubility compared with PAA and PAM makes PAN more difficult to dissolve in high concentrations.

We have explored binders, the hidden facilitators behind battery performance. In this feature, we covered not only the characteristics of aqueous and non-aqueous binders, but also the latest requirements for binders. We will continue to introduce various materials that contribute to better battery performance in our “A Better Life with Batteries” series.