✍️Professor Dong-Wan Kim

Department of Battery-Smart Factory, School of Civil, Environmental and Architectural Engineering, Korea University

History and Operating Principles of Lithium–Sulfur Batteries

Discovered around 2000 B.C., sulfur (S) is documented in historical records as having been used in ancient societies for religious rituals, bleaching, air purification, disease treatment, and firearm manufacturing. Scientific research on sulfur advanced in the 17th and 18th centuries, during which sulfuric acid (H2SO4) was identified as one of its principal compounds. In 1894, sulfur extraction from mines began using the Frasch method, developed by American chemist Herman Frasch.

Sulfur accounts for approximately 0.06% of the Earth’s crust. It can be found in nature in fossil fuels such as coal and natural gas, and exists either as a free element or in the form of compounds with major metals such as iron, copper, and zinc. In particular, the chemical combination of lithium (Li) and sulfur (2Li + S → Li2S) was first patented in 1962 by Herbert Danuta and Ulam Juliusz, laying the foundation for a new battery technology. It was initially limited to primary batteries due to the irreversible formation of electrolyte by-products. However, in the late 1980s, the development of modified electrolytes incorporating solvents such as dioxolane enabled research into secondary batteries.

Lithium–sulfur batteries are rapidly emerging as strong competitors to lithium-ion batteries in energy storage. They offer a theoretical energy density of 2,600 Wh/kg and have the potential to reach 500 Wh/kg in practical cells. In addition, their advantages—including abundant raw materials, cost competitiveness, low environmental impact, lightweight design, and long-duration operation as rechargeable batteries—are being increasingly highlighted. Along with technological advancements, lithium–sulfur batteries have become sufficiently practical to be deployed in experimental aircraft.

Challenges and Technological Trends in Lithium–Sulfur Batteries

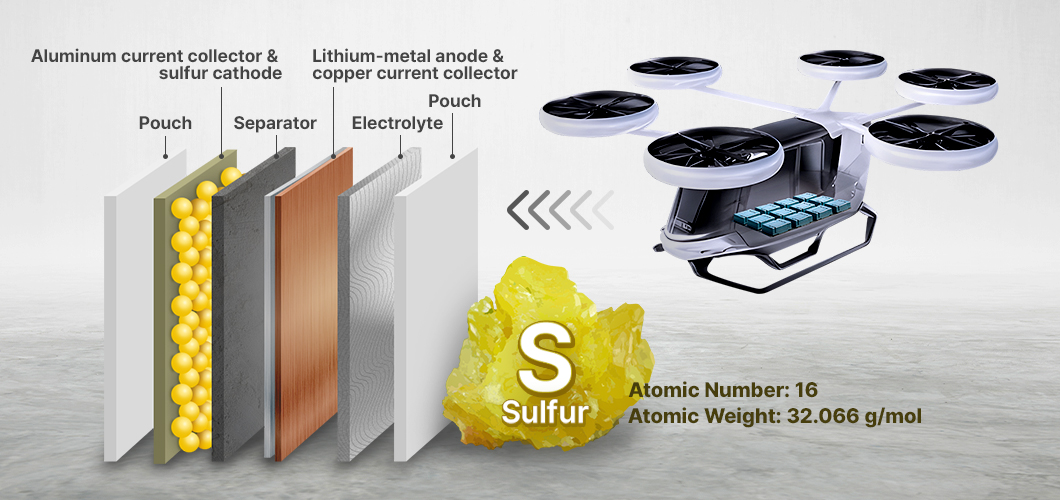

Several challenges must be addressed before lithium–sulfur batteries can be commercially deployed. A typical lithium–sulfur battery cell consists of a lithium-metal anode, an organic liquid electrolyte, and a sulfur composite (S8) cathode. During discharge, sulfur is reduced to lithium sulfide, the final discharge product, through a two-step process.

Step 1: S8 (solid) → Li2S6 (liquid) → Li2S4 (liquid)

Step 2: Li2S4 (liquid) → Li2S2/Li2S (solid)

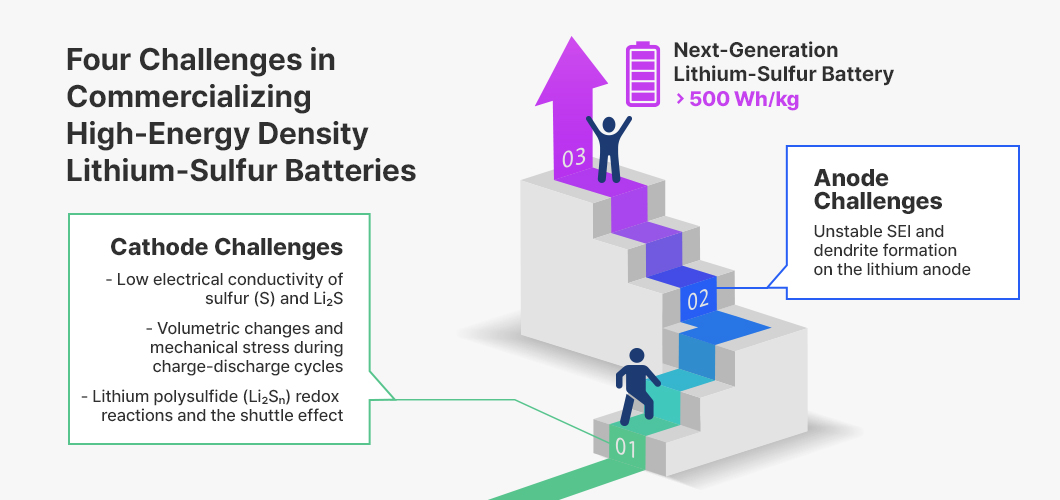

Such sequential and complex redox reactions give rise to several challenges that must be addressed for the commercialization of lithium–sulfur batteries. The main challenges can be summarized into the following four points.

(1) Low electrical conductivity: The inherently low electronic conductivity of sulfur and Li₂S, associated with high sulfur loading1 in the cathode, can limit battery performance.

(2) Volumetric change: The volumetric change during the S ⇌ Li₂S conversion can induce mechanical stress and slow lithium-ion transport.

(3) Shuttle effect2: The shuttle effect, caused by the dissolution of lithium polysulfides in the electrolyte, can lead to active sulfur loss, self-discharge, and reduced cycle life.

(4) Lithium anode stability: The lithium-metal anode is prone to the formation of an unstable solid electrolyte interphase (SEI) and dendrite growth, which can lead to lithium corrosion and hinder anode thinning.

*View Battery Glossary – Dendrites

Extensive research and development efforts are underway to address various challenges with the aim of maximizing the potential of lithium–sulfur batteries. Key technological directions include the development of functional sulfur hosts with high electronic and ionic conductivity and porous structures3, as well as the application of materials that can adsorb and anchor lithium polysulfides while catalyzing electrochemical reactions. In addition, artificial protective layers are being designed to stabilize the SEI on the lithium anode and restrict dendrite formation. These research efforts are expected to facilitate the practical application and commercialization of lithium–sulfur batteries.

A wide range of companies are conducting or supporting research to overcome the limitations of lithium–sulfur batteries and advance their commercialization. The Energy Materials Laboratory at Korea University is collaborating with LG Energy Solution on the development of composite nanostructured catalysts to accelerate the reversible redox reactions of lithium polysulfides.

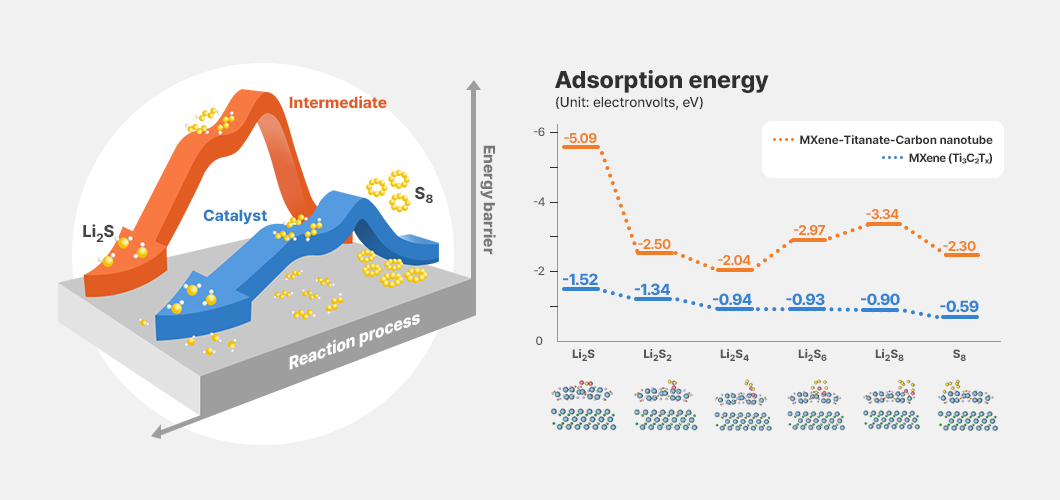

The project recently developed a composite MXene–titanium oxide–carbon nanotube catalyst that improves cycling performance as well as charge and discharge rates by significantly reducing the adsorption energy4 of lithium polysulfides, even at high specific surface area. Test results demonstrated stable cycling performance over more than 500 cycles at a 5C rate (12-minute charge).

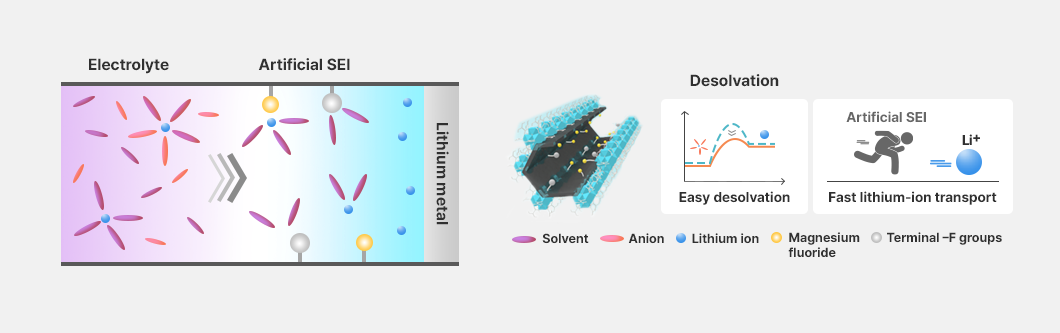

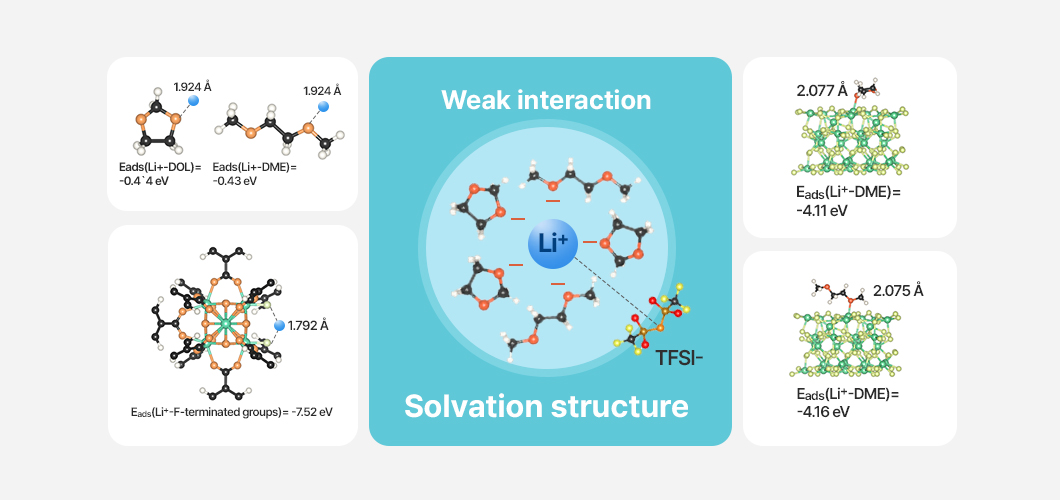

Another research approach involves forming an artificial protective layer based on a magnesium fluoride–incorporated metal–organic framework (MOF) on the surface of the lithium anode. This approach leverages high lithophilicity, enhanced lithium-salt dissociation, and effective desolvation reactions to maximize the suppression of lithium dendrite formation and the improvement of lithium-ion transport.

The academia–industry project further developed novel lithium polysulfide conversion catalysts and long-life lithium anodes incorporating covalent organic framework–based artificial protective layers, which were subsequently integrated into and validated in lithium–sulfur batteries.

Global Market Size and Next-Generation Strategies for Lithium–Sulfur Batteries

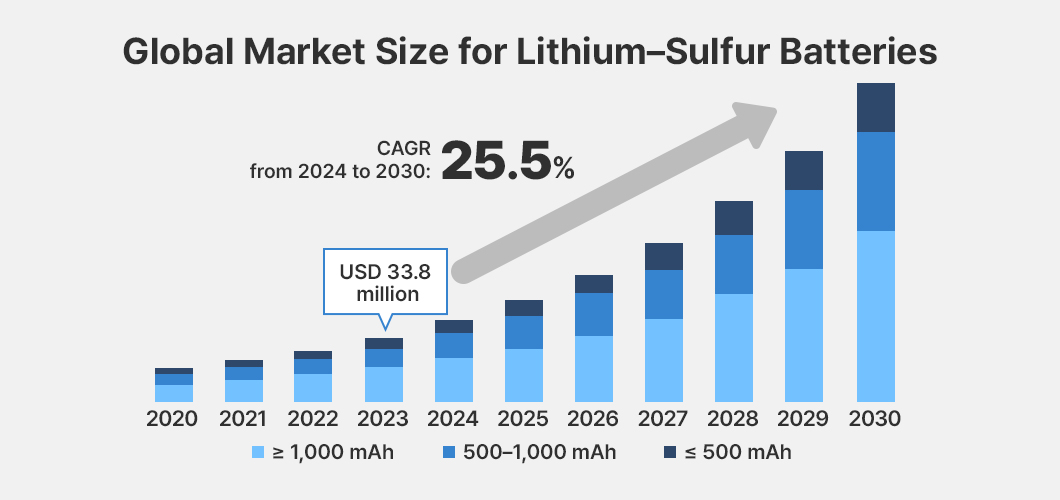

The lithium–sulfur battery market is primarily driven by growing demand for high–energy-density storage solutions. In particular, demand from electric vehicles (EVs) and portable electronic devices is leading market growth, while aerospace applications and grid-scale energy storage systems are also expected to account for a significant share. Accordingly, the global lithium–sulfur battery market size is estimated at approximately USD 33.8 million, with the compound annual growth rate (CAGR) projected to reach 25.5% between 2024 and 2030.

Recently, solid-state lithium–sulfur battery technologies employing solid electrolytes have been proposed to suppress the shuttle effect of lithium polysulfides in liquid-electrolyte lithium–sulfur batteries, with reports demonstrating cycling stability exceeding 25,000 cycles. The introduction of solid-state electrolytes and hybrid electrolytes is expected to represent another significant technological turning point.

Lithium-sulfur batteries can extend driving range and cut operation costs even at the same size and weight, due to their theoretically high energy density and lightweighting compared to conventional lithium-ion batteries. Coupled with intensive technological development, long-term investment, and commercialization efforts by companies, lithium-sulfur batteries are increasingly likely to establish themselves as a core power technology for aerospace applications, electric aircraft (including eVTOL), and long-range EVs after 2030.

Furthermore, lithium–sulfur batteries are gaining attention as low-cost and environmentally friendly secondary batteries because they use sulfur—a by-product of oil refining—while eliminating the use of nickel, cobalt, and manganese, which are key raw materials in lithium-ion batteries. In alignment with global carbon-neutral policy initiatives, lithium–sulfur batteries are projected to emerge as a key technology driving a paradigm shift in the energy industry.

※ The views expressed in this column are those of the author and do not necessarily represent the official position or strategy of LG Energy Solution.↩︎

- Loading: The amount of a substance adsorbed onto another material or attached to a supporting substrate. ↩︎

- Shuttle effect: A recurring phenomenon where soluble intermediate lithium polysulfides (such as Li2S6 and Li2S4) diffuse to the lithium-metal anode, in which they are reduced and precipitate as solid Li2S2 and Li2S while simultaneously soluble lithium polysulfides are regenerated in the electrolyte, and re-diffuse back to the cathode driven by the concentration gradient. ↩︎

- Porous structure: A networked structure in which pores (void spaces) are three-dimensionally distributed throughout a solid material. Because the material is not fully dense, pores of various sizes are present, which increases the surface area, provides diffusion pathways for mass transport, and enhances adsorption capability. When applied to the cathode of lithium–sulfur secondary batteries, this structure can trap active sulfur particles or lithium polysulfides within its pores, thereby inhibiting the shuttle effect, enabling higher sulfur loading, and facilitating smooth lithium-ion transport. As a result, it contributes to improved high-rate charge–discharge performance. ↩︎

- Adsorption energy: The amount by which the system energy decreases as a result of physical or chemical interactions between an adsorbent surface and adsorbates during the binding process of adsorbates such as gases, ions, or molecules to adsorbents such as a solid surface. ↩︎